To tackle the housing crisis, the Australian Government, in collaboration with state and territory governments, has set an ambitious goal through the National Housing Accord to build 1.2 million new and well-located homes between 1 July 2024 and 30 June 2029.

However, hitting that 1.2 Million Homes Target seems unlikely to happen.

In this blog, we’ll uncover the three key reasons why this ambitious goal could fall short. Ready to find out? Let’s dig in!

Housing completion has been falling behind

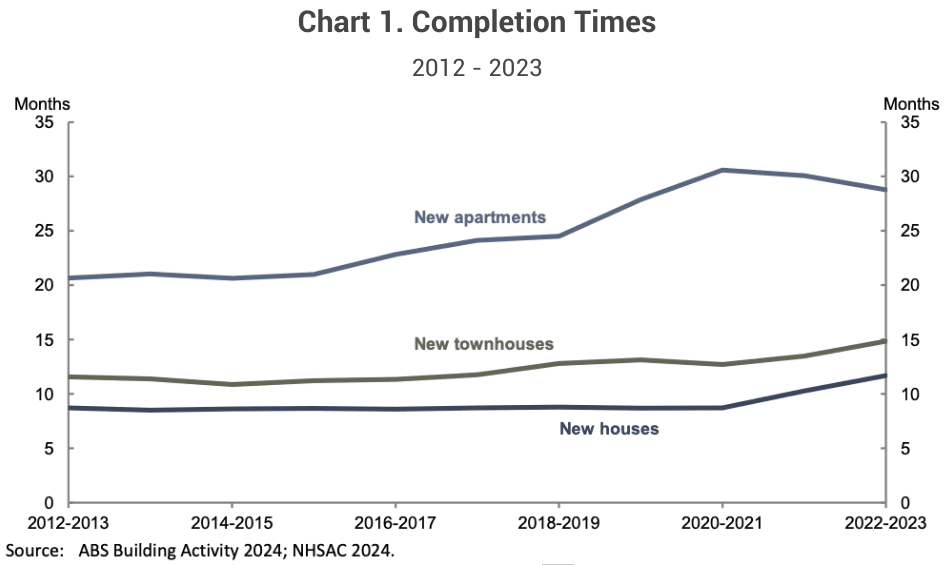

For simplicity, let’s assume that the average time to build a dwelling is one year. This means that the number of building approvals in 2023 roughly equals the number of completions in 2024. However, it’s important to notice that different types of dwellings have varying construction timelines. These can range from a few months to several years, depending on the type of property. For example, in 2023, houses typically took about 12 months to build, while higher-density dwellings took longer time (townhouses – 15 months and apartments – 29 months) (Chart 1).

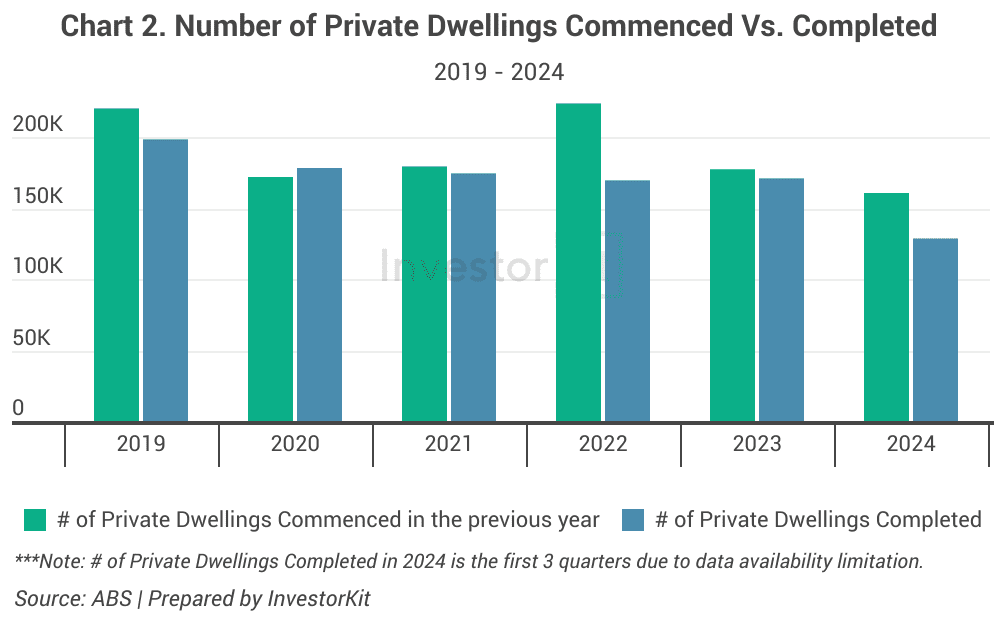

From 2019 to 2024, housing completions lagged behind commencements, except in 2020. The biggest gap occurred in 2022, when 224,117 housing development projects started in the previous year, but only 169,949 were completed, resulting in a 24% shortfall. In 2024, while we only have 9 months’ worth of data, we’ve already seen a 20% shortfall. The number of unfinished projects keeps rising.

Building approvals didn’t meet targets

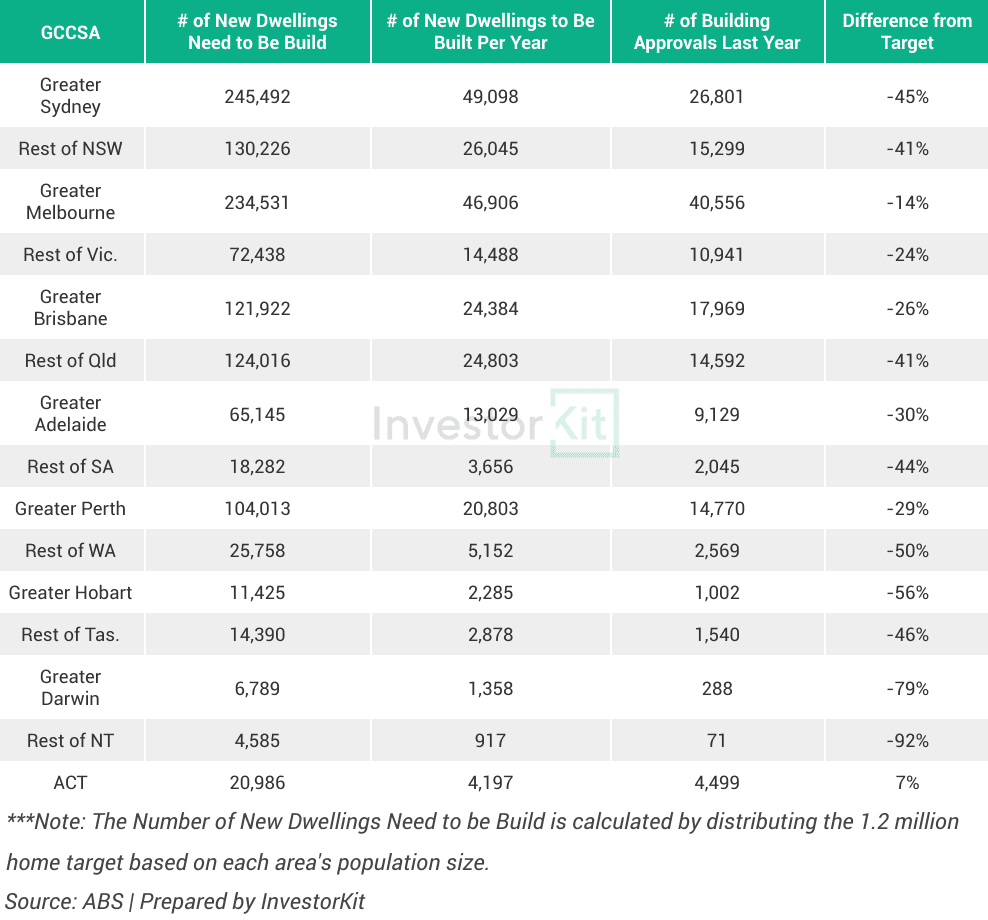

Since construction timelines vary, with some projects taking years, to meet the 1.2 million dwelling goal by 2029, we need to secure more than one-fifth of the total building approvals annually in the first three years, allowing additional time for high-density projects to complete. However, this is far from reality. In 2024, Australia needed at least 240,000 new dwelling building approvals, yet only 162,071 building approvals were issued, a 32% shortfall from the year’s target.

When breaking down the target by region, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) is the only state/territory on track to meet its first-year goal. Among the rest, Melbourne performed best with a shortfall of just 14%, while Darwin struggled the most with the biggest gap of 79%. Sydney, home to the largest population, saw a 45% shortfall, worse than most other capital cities (see table below).

At the SA3 level, about 85% of regions failed to hit their first-year targets.

Areas like Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach in Gold Coast, Caloundra in the Sunshine Coast, Geelong, Maitland and Hervey Bay are performing well, while Tweed Valley (-76%), Gladstone (-76%), Mackay (-75%), Bathurst (-73%), Port Stephens (-69%) are at the bottom.

Projection result doesn’t look optimistic either

According to the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, housing supply is expected to fall short of demand over the next six years (2023/24 to 2028/29). After accounting for demolitions, only 1,040,000 new dwellings are projected, well below the 1.2 million target.

What are the causes?

1. Elevated construction costs (material and labour costs)

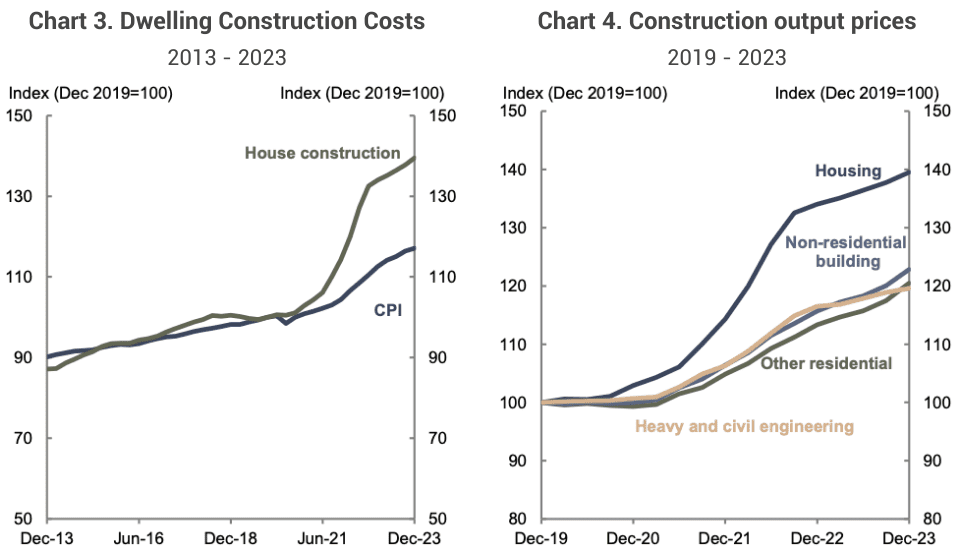

Rising construction costs have been a major cause behind the constrained supply. The cost of building a new home is about 40% higher than pre-2020 levels, outpacing general price increases by more than 20% (Chart 3). Within the construction sector, housing has faced the most severe cost pressures compared to other segments (Chart 4).

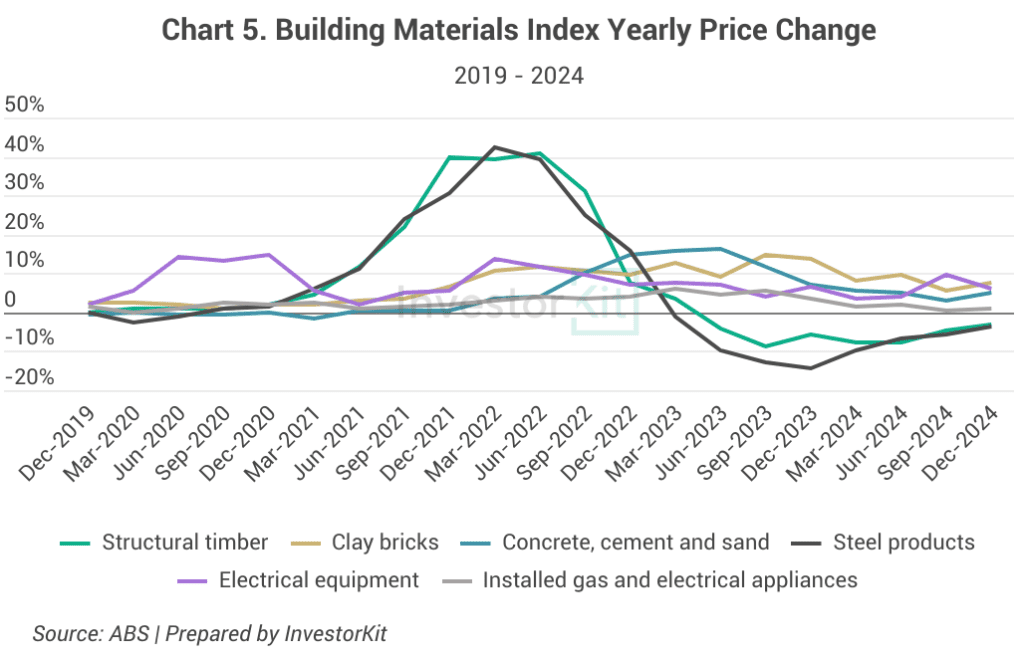

Rising Material Costs: An increase in building material prices was a major driver of construction cost rises since 2020. The growth has now slowed, but the prices are still elevated: according to ABS, in December 2024, prices for building materials used in house construction recorded a small rise of around 1.6%. While price growth for structural timber, steel products and electrical equipment have slowed down, costs for components such as clay bricks, installed gas and electrical appliances, concrete, cement and sand are trending up (Chart 5).

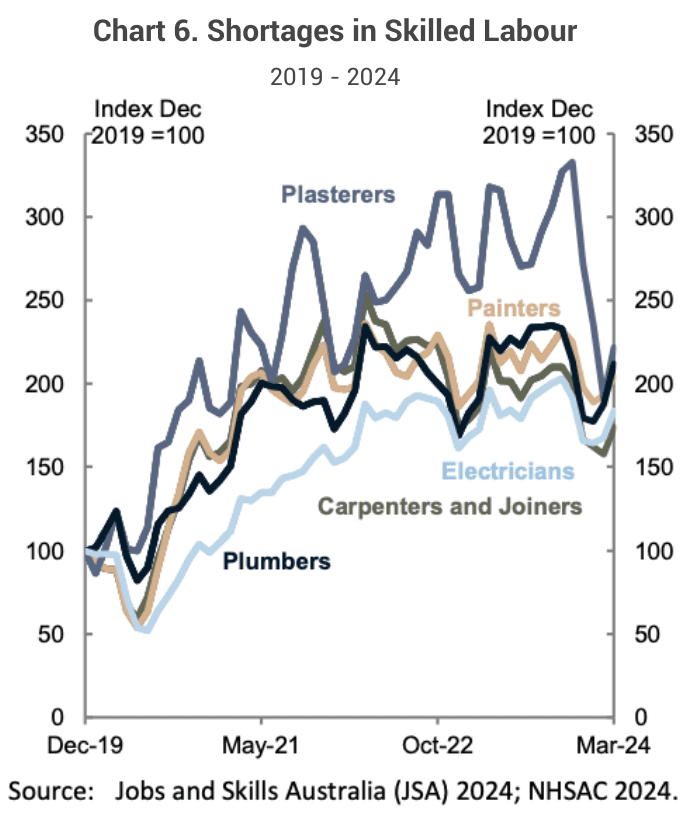

Rising Labour Costs: Long-term shortages of skilled workers in residential construction continue to push up costs, intensified by competition from government projects and private industry. Private sector construction wages rose 3.5% in the year to December 2024, higher than the private sector average (3.3%), with acute shortages in bricklaying, roofing, carpentry, and tiling (Master Builders Association). Skilled trade vacancies remain significantly elevated, about 75% to 125% higher than five years ago, though they have eased slightly from early 2023 peaks (Chart 6) (Jobs and Skills Australia, 2024).

2. Reduced land supply and increased land prices

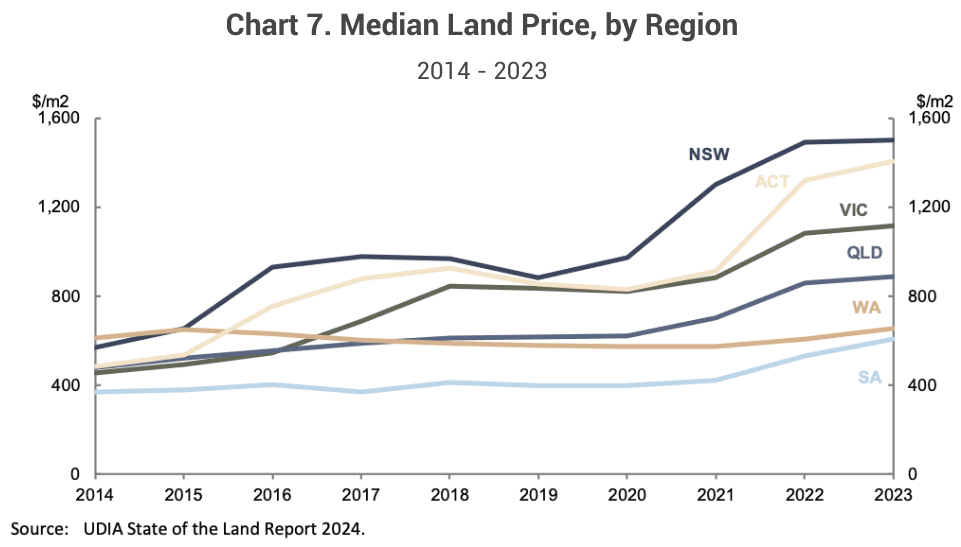

The release of new subdivided land declined in 2023, limiting opportunities for new housing construction. The number of residential greenfield lots (new land, primarily used for detached homes) dropped 26% nationwide to just 36,500 (UDIA, 2024). This marks a 33% drop from the 10-year average, tightening supply and driving up land prices. As a result, the average capital city land price has now surpassed $1,000/m², with costs ranging from $1,505/m² in Greater Sydney to $608/m² in Adelaide (UDIA, 2024) (Chart 7).

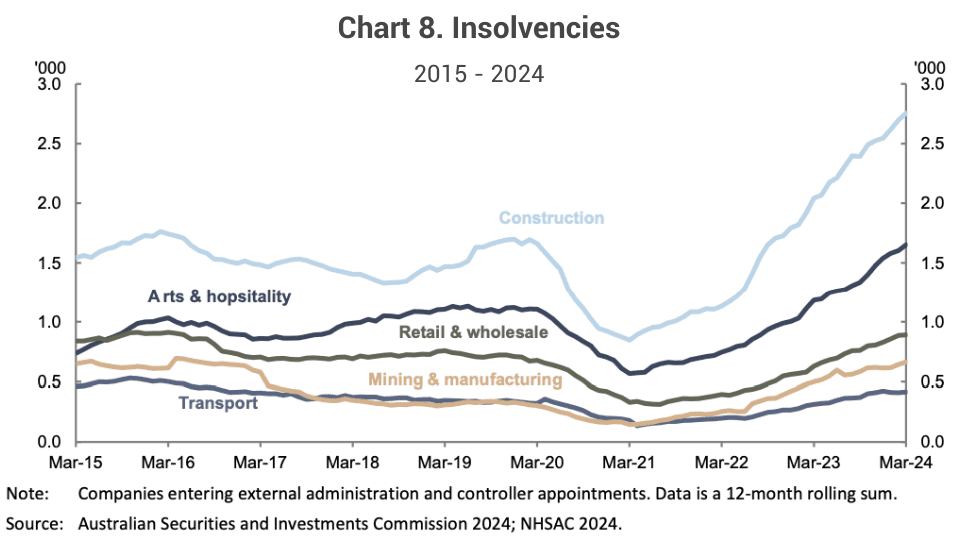

3. Increased insolvencies in the construction industry

Typically, soaring house prices would induce new supply by increasing developer profits. However, over the past two years, rising input costs and fixed-price contracts have squeezed profit margins, pushing many construction firms into financial distress. Insolvencies have surged, hitting the construction sector the hardest (Chart 8). The share of builders with negative cash flow has climbed to 30%, well above the usual 20%, reaching its highest level in over a decade.

Signs of Stability, but Challenges Remain

Industry conditions are beginning to stabilise, with insolvency rates returning to typical levels as material cost increases normalise. Nevertheless, industry stakeholders argue that media coverage of insolvencies has weakened consumer confidence and deterred potential workers from entering the field. Additionally, some builders have exited the industry due to shrinking margins, while others have shifted to niche markets where they can charge a premium, moving away from cheaper and high-competition markets with lower profitability.

In a nutshell…

Rising construction costs, limited land supply, and increasing insolvencies in the construction sector are the key drivers of Australia’s housing shortage. With dwelling unit completions and building approvals falling short of expectations, the 1.2 million-home target by 2029 is becoming increasingly unrealistic.

However, this persistent undersupply creates a favorable environment for market growth. Investors shouldn’t be discouraged by the government’s ambitious supply targets, as they are unlikely to be met. With demand outpacing supply, waiting on the sidelines could mean missing out on the opportunities as prices continue to rise.

This blog is inspired by InvestorKit podcast episode, “Why Australia’s 1.2 Million Homes Target is Unlikely to be Met”. Tune in now for more detailed discussion by clicking here!

Many of the charts and data in this blog are cited from the State of the Housing System 2024 report. This is an annually released free report by the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council. Check it out for more insights in the report!

At InvestorKit, we dedicate ourselves to cut through market noise with deep data analysis, helping our clients make clear and informed investment decisions. As housing supply remains tight, there’s no better time than now to invest in properties. Would you like to start growing your portfolio with confidence, backed by solid research and experienced specialists? Let’s get started today by clicking here and requesting your 15-minute FREE no-obligation discovery call!

.svg)